“You Don’t Only Have to Work There. You Have to Live There.”- Living Underwater with Former Aquanaut Roger Garcia (DEEP)

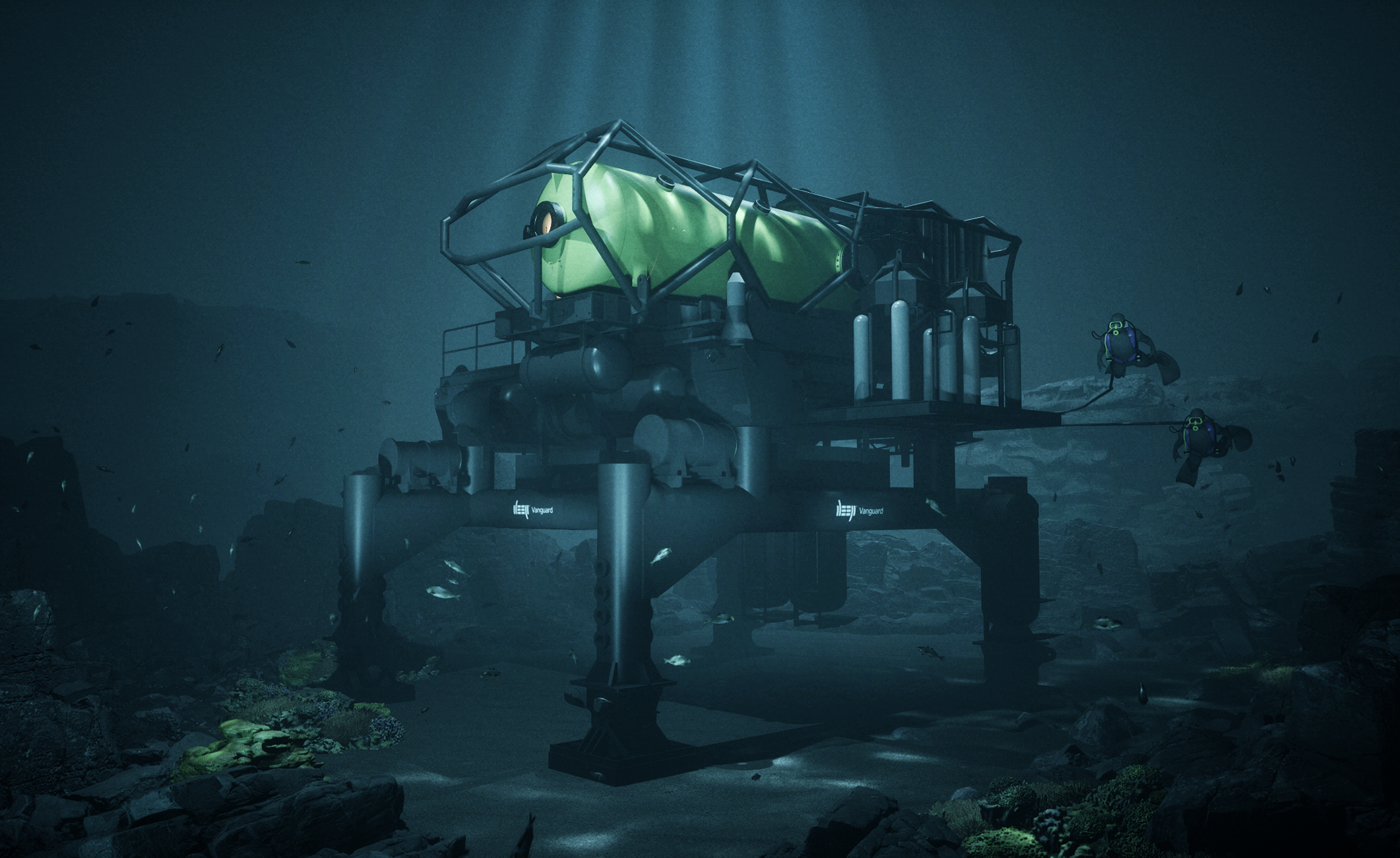

DEEP’s Vanguard subsea habitat, designed for extended human presence underwater.

Image credits: DEEP

When people think about extreme environments, underwater is often one of the last that comes to mind. After all—who actually lives underwater?

The answer is aquanauts.

As part of my ongoing research for Extreme Living, I’ve been exploring how humans function in environments that are physically and psychologically constrained. One of the environments I reference on the site is underwater habitation. To understand it more deeply, I spoke with Roger Garcia, who has spent more than two decades working in underwater habitats, first as an aquanaut living inside them, and later leading operations. He is now part of DEEP, one of the companies shaping the next generation of subsea habitats.

You might wonder: what do people actually do underwater?

Research, scientific exploration, technology testing—and in many cases, training for space missions. Underwater habitats have long served as powerful analogs for spaceflight, precisely because they combine confinement, isolation, operational risk, and reliance on engineered life-support systems.

That’s what makes them such a revealing environment to study.

Intent Changes How Confinement Is Experienced

Confinement is unavoidable underwater. There’s no denying that. Space is limited, movement is restricted, exits are delayed, and the environment outside is unforgiving.

But one of the most important insights that emerged from my conversation with Roger Garcia is that intent changes how confinement is experienced.

There is a significant difference between having to be somewhere and choosing to be there. Basically being forced into one v/s choosing to enter. The aquanauts and researchers who live underwater are highly trained, mission-driven, and deeply motivated. They know why they are there, and they want to be there.

Because of that, the psychological weight of confinement is reduced. It doesn’t disappear—but it’s experienced differently. For these individuals, confinement alone isn’t what makes long-duration stays difficult.

So what makes it?

The In-Between Is Where It Gets Hard

Roger Garcia inside the Aquarius Reef Base during a saturation mission — the everyday moments between work that define long-duration living underwater.

Image credits: Roger Garcia

The real challenge emerges in the in-betweens.

Work underwater is structured. Tasks are clear. Purpose is explicit.

But life doesn’t end when the workday does.

The hardest moments are often:

after the work is finished

before going to sleep

during downtime

when there’s nothing to “do” except exist in the space

It’s in these in-between moments that confinement becomes heavier. This is where erosion can happen, psychologically, socially, emotionally.

As Roger put it plainly: you don’t only have to work there. You have to live there.

This is where the distinction between livable and habitable becomes meaningful.

From Livable to Habitable

Living quarters inside a subsea habitat, spaces that must support recovery, routine, and daily life, not just mission tasks.

Image credits: DEEP

A livable environment allows people to function.

A habitable environment allows people to endure.

Livability ensures that tasks can be completed and systems can operate. Habitability goes further. It asks whether people can remain psychologically intact over time—whether they can recover between work cycles, interact positively with others, and sustain daily life without erosion.

When we ask humans to live inside environments that are inherently challenging and constrained, it raises a larger responsibility. If we are deliberately placing people into conditions that demand endurance, is it not our obligation to make that experience as humane and supportive as possible, wherever we can?

Habitability isn’t about completing a single mission. It’s about sustaining human life between missions, days, and tasks. It’s about what happens in the moments when the work is done but the environment remains.

What was refreshing about the conversation with Roger was how strongly he emphasized habitability, not as an abstract design ideal, but as something that shows up in everyday life underwater. Again and again, his examples reinforced the same idea: if people are going to live in these environments for extended periods of time, survival alone isn’t enough.

If habitability is about sustaining human life over time, then the question becomes more practical: what actually makes that possible, day to day?

Roger didn’t answer this in terms of systems or specifications. Instead, he kept returning to how the environment feels once the work is done, both at the end of the day and at the end of the mission.

After the Workday: Comfort

Comfort, in his view, isn’t a luxury. It is what allows people to recover, interact positively, and remain grounded inside a confined space.

Comfort reduces friction. It supports recovery. It makes positive human interaction possible day after day. And it signals that an environment was designed with long-term human presence in mind, not just short-term survival.

Roger was clear about this distinction. “When you’re working, it’s one thing,” he said. “But when you come back in, you also have to live there.” If the living environment doesn’t support recovery and positive interaction, the experience begins to erode, no matter how well the engineering performs. In that sense, comfort becomes part of the system that allows people to function over time.

After the Mission: The Return

There was one simple way Roger measured whether an environment had crossed the threshold from livable to habitable: people wanted to come back.

At the end of underwater missions, he often observed a mix of emotions. Crews were ready to return to the surface, see their families, and feel the sun again. But many also wished they could stay longer. Others actively looked forward to returning for another mission.

That desire to return wasn’t incidental. It was a signal that the environment had moved beyond being merely livable. It had become habitable.

How Do You Get There? Listen First.

NEEMO 20 Crew - Decades of underwater habitation, experience that continues to inform how new habitats are designed.

Habitability isn’t guesswork. It’s learned through decades of lived experience.

Underwater habitation has a rare advantage: decades of lived experience. Programs like Aquarius alone involved hundreds of participants over nearly sixty years. That’s not anecdotal, that’s a database.

Roger was emphatic about this: listen to the people who lived there. Ask what worked. Ask what didn’t. Use that knowledge to inform design decisions, operational protocols, and future habitats.

The challenge isn’t a lack of information. It’s whether we choose to listen.

A Shift Is Already Underway with DEEP

Interior of DEEP’s Vanguard habitat, where spatial flow, comfort, and daily life are treated as core components of human performance underwater.

Image credits: DEEP

What made this conversation particularly compelling is that this shift is already happening.

Companies like DEEP are moving away from purely equipment-driven environments and toward habitats designed around human experience, how spaces flow, how people interact, how life unfolds between work cycles.

This isn’t about abandoning safety or engineering rigor. It’s about recognizing that long-term human habitation requires more than survival systems.

For readers interested in the current generation of subsea habitats discussed here, more information on DEEP’s Vanguard habitat can be found on their website.

What Comes Next

Achieving truly habitable environments isn’t about one design move or one discipline. It requires multiple supports or the way I like to call is multiple scaffoldings working together. Something I’ll explore more deeply in the next piece.

For now, the question is simpler, and more important:

When humans live underwater, are we designing spaces they can merely endure or spaces they can actually live in?

If you’d like to hear the full story in Roger’s own words, our conversation is on the Extreme Living podcast.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/1WhxdhSAeTQ3u5tLhSYmfE