When You Forget How to Decide: Decision Fatigue After Isolation

Inside the HERA habitat, daily life is governed by a fixed timeline. Tasks are sequenced, procedures are predefined, and individual decision-making is intentionally minimized to preserve focus and safety.

Image credits: Andrzej Stewart.

In previous articles, we explored how conflict accumulates in confined environments and how architecture might help people recalibrate under pressure. But there's another challenge that emerges in extreme isolation—one that doesn't reveal itself until after the mission ends.

You forget how to make decisions.

Not because you've lost cognitive ability.

Not because you're tired or confused.

But because for months, you haven't had to decide at all.

When Not Deciding Is The Design & Certainly Not a Restriction

You haven’t had to make a decision because there was structure in place. And that structure isn't a flaw, it's essential. Analog missions depend on it. Without structure, a closed system can't stay safe or functional.

As Andrzej described it, you're handed a schedule each day. You follow it. The timeline comes with procedures, and you execute them. That's not restriction, it's support.

In extreme environments, removing everyday decisions isn't about control. It's about preserving mental energy for what actually matters: staying safe, doing the science, working as a team, enduring.

Choice is not a luxury the system can afford.

Structure as cognitive scaffolding.

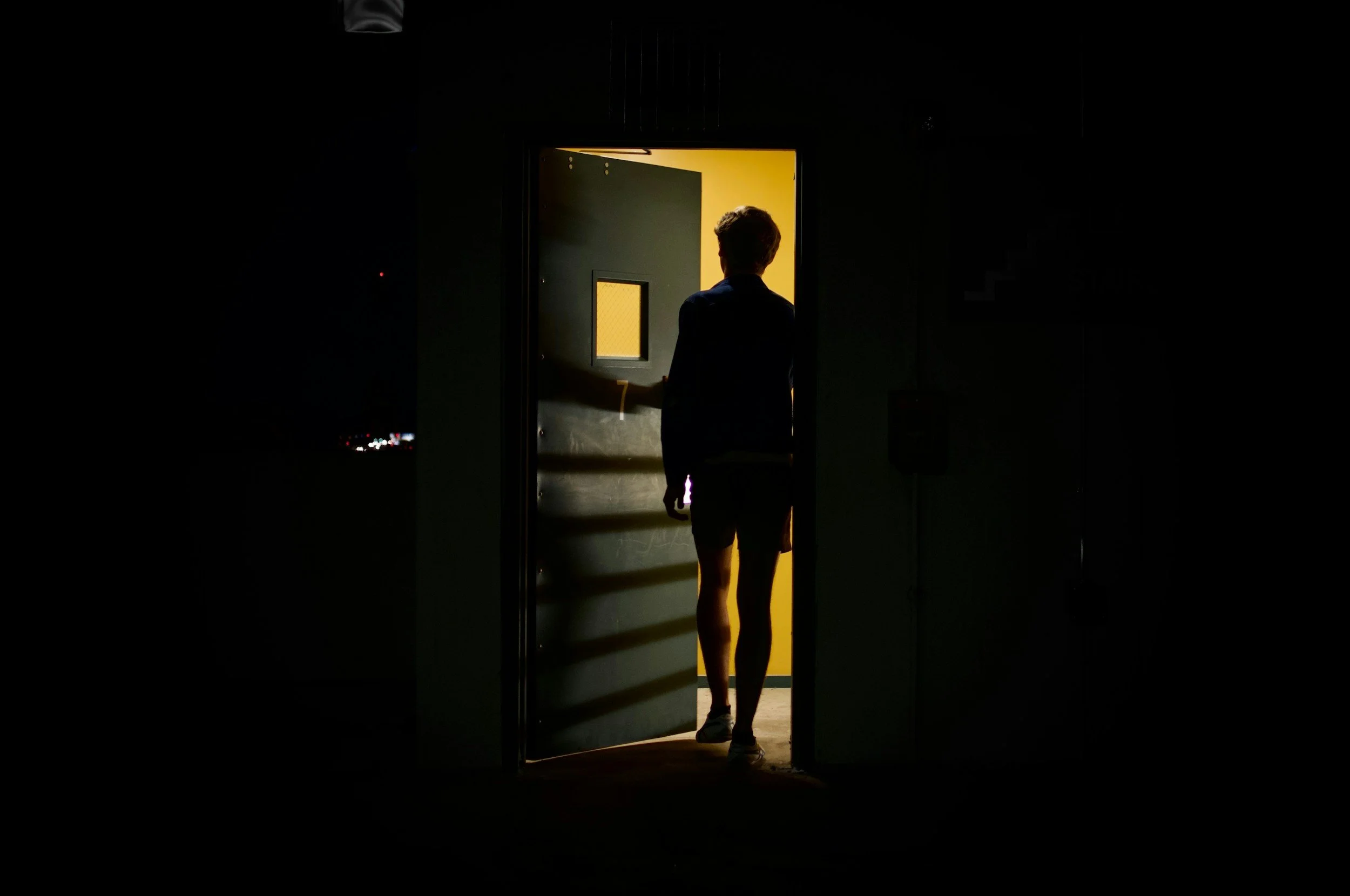

Standing in the Grocery Store

After long periods without decision-making, even mundane options can feel cognitively overwhelming.

During my conversation with analog astronaut Andrzej Stewart, he described something that caught me off guard. After spending a year in the HI-SEAS Mars simulation habitat, he found himself standing in a grocery store, staring at a wall of dental floss.

Thirty different types.

He couldn't remember how any of it was supposed to get into his cart.

"I don't know," he said. "NASA just issued this to me. Now I have to choose which one."

It sounds minor, almost humorous. But it points to something deeper about what happens when you live in a highly structured environment for an extended period.

In analog missions, and in actual spaceflight, astronauts don't make many decisions for themselves. They're handed a timeline each day, a detailed schedule with procedures to follow. Every task is planned. Every moment accounted for. You wake up, you execute the plan, you go to sleep.

"You're not really making decisions," Andrzej explained. "You're executing the timeline that you're given."

For days, weeks, or in his case an entire year, decision-making atrophies or weakens. Not from lack of intelligence, but from lack of practice.

The Invisible Load of Choice

Too many choices, too suddenly—the cognitive overwhelm of re-entry

We don't typically think of decision-making as a skill that needs maintenance. But it is.

And in everyday life, we're constantly exercising it, often without realizing the cumulative weight.

What to eat.

What to wear.

Which route to take.

What task to prioritize.

Whether to respond to that email now or later.

What brand of dental floss to buy.

These aren't major decisions, but they add up. Psychologists call this decision fatigue, the deteriorating quality of decisions after a long session of decision-making. Studies suggest judges may grant parole more frequently earlier in the day, though the exact causes are debated. In healthcare settings, doctors demonstrably make more conservative choices as their shifts progress, ordering fewer tests, making safer referrals. We all know the exhaustion of too many choices.

But what Andrzej experienced was the opposite side of that coin: decision atrophy or a weakness. When you've been relieved of choice for months, re-entering a world of infinite options is disorienting.

The grocery store wasn't just overwhelming because of the variety. It was overwhelming because his brain had stopped practicing that particular form of executive function.

Because suddenly he was required to decide again, not in small increments, but in a flood.

How Andrzej Adapted

After his HERA mission—a shorter, 14-day simulation, Andrzej wasn't prepared for the cognitive shift. "A couple of days after I got out, I was starting to hear about bills that needed to be paid and chores I would have to do. And you have to kind of learn how to make those decisions again."

He learned to anticipate this for subsequent missions. Before coming out of HI-SEAS, he warned friends and family: "I'm going to need a few days before I'm fully engaging with you again. I'm just getting used to being out in the real world right now."

That warning, that buffer, mattered. It gave him space to rebuild the decision-making skill gradually rather than being thrust into full autonomy immediately.

There's value in structure. During high-stress, high-stakes situations, having clear procedures prevents dangerous improvisation. In space, following the timeline keeps missions on track and crews safe. In hospitals, protocols save lives.

The problem isn't structure itself. It's the sudden removal of it without transition.

Re-Entry As A Shared Pattern

Re-entry is a threshold moment. Leaving a highly structured system often means crossing abruptly from guided action into full autonomy.

This pattern isn't unique to space simulations.

Think about healthcare workers operating within rigid protocols during 12-hour shifts in trauma units or ICUs. Their days are structured by patient needs, physician orders, and emergency response procedures. Research into what happens when they transition back to personal decision-making after intense shifts would reveal valuable insights.

Or consider correctional facilities. Incarcerated individuals have almost no autonomy over daily decisions, when to eat, what to wear, where to be, what to do. Upon release, they're expected to immediately navigate employment, housing, transportation, finances, and social relationships. The decision-making muscle hasn't been used in years.

The parallel extends to long-term care facilities, military deployments, and even extended hospital stays. These are psychologically confined environments where structure replaces choice.

This is something I want to research further by talking directly to people working in these environments—healthcare workers, nurses, correctional program staff, military personnel—specifically about decision-making transitions. We might uncover design interventions that haven't been considered yet.

In space missions, there's already some acknowledgment of this. Astronauts returning from the International Space Station go through reintegration support—medical monitoring, debriefs, family time. But much of that focuses on physical readjustment (bone density, muscle strength, balance) rather than cognitive and psychological reintegration.

What if we treated decision-making like any other skill that needs rehabilitation after disuse?

Can We Design for the Transition?

If spaceflight has taught us anything, it’s that re-entry cannot be left to chance. The question is not whether reintegration support matters—but what kind of reintegration we prioritize.

Could a gradual reintroduction of choice in the final weeks of a mission ease re-entry?

Would post-mission schedules that slowly hand autonomy back make a difference?

These questions point toward a need for deeper research.

In healthcare, what does the transition from "protocol mode" to "personal mode" actually look like after long shifts? How do staff manage that cognitive shift?

In correctional systems, what would practicing decision-making in low-stakes environments look like before release? How might graduated autonomy compare to immediate full independence?

These questions point to a broader principle: if an environment removes decision-making for an extended period, shouldn’t the transition back be designed rather than assumed?

Closing Thought

Decision-making isn't just about having options. It's about having practice.

Extreme environments teach us that. Confinement, whether physical or psychological, often means living within systems that decide for you. And while that structure brings clarity and focus during the mission, it creates a challenge afterward.

The question isn't whether structured environments are good or bad. It's whether we're designing the exits as carefully as we design the entries.

Because eventually, everyone has to stand in front of that wall of dental floss. And if we know that moment is coming, maybe we can make it a little less overwhelming.

Next in this series

When confinement ends, it's not just decision-making that returns—sensory stimulation floods back too. Movement, noise, unpredictability. Everything that was muted suddenly amplifies. What happens when your nervous system has to recalibrate to the world again?

If you’d like to hear the full story in Andrzej’s own words, our conversation is on the Extreme Living podcast.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/5JZNjVQHCgKieq0qiWf501?si=0T1ZK4WQRg2woAc1fP25ZQ