When Pressure from Conflict Has Nowhere to Go: Translating Healthcare Design to Analog Habitats — Lessons From Andrzej Stewart

The HI-SEAS habitat on Mauna Loa — a sealed environment designed for sustained confinement and operational focus.

Image credits: Andrzej Stewart.

Continuing from the Architecture of Conflict

In the previous piece, we explored how conflict in long-duration missions becomes emotional pressure when there’s no way to walk away from it. That pressure doesn’t dissipate, it accumulates. Sitting with that idea made me wonder how other extreme environments prevent this kind of pressure from spreading when escape isn’t an option.

I found myself returning to healthcare spaces, a parallel I’ve written about before. Early in my career as an architect, I worked on a cancer center for two years, an environment that operate under sustained psychological strain. In cancer centers and trauma units, pressure doesn’t spike occasionally; it is continuous. And much of that burden falls on nurses.

Drawing Parallels: The Architectural Response in Healthcare

In healthcare settings like cancer centers and trauma units, pressure comes from multiple directions at once. From what I’ve observed, it rarely stems from a single source. Instead, it accumulates through three overlapping forms of pressure:

Task pressure

Life-critical decisions, sustained cognitive load, and the responsibility of operating in environments where mistakes carry real consequences.Interpersonal pressure

Continuous interaction with patients, families, and colleagues, coupled with the emotional labor of delivering difficult news and absorbing others’ distress.Sensory and environmental pressure

Noise from alarms and equipment, constant movement, visual chaos, and the absence of true downtime in spaces where intensity is ever-present.

Designers respond to this condition by building what are commonly referred to as quiet rooms for nurses, small, dedicated spaces meant to reduce overstimulation and absorb emotional pressure before it spills back into the system. These spaces are not amenities or luxuries. They function as pressure-release valves embedded directly into the architecture.

Quiet rooms in healthcare are designed to help staff de-stress, recalibrate, and recover amidst high-pressure environments. Features often include dim lighting, controlled acoustics, natural imagery, and comfortable seating, all aimed at supporting nervous-system regulation. The intent is not escape, but reset: a brief interruption that allows pressure to dissipate rather than accumulate.

In a future piece, I plan to look more closely at how different hospitals design these quiet rooms, comparing a small set across projects to understand how variations in layout, materiality, and placement shape how pressure is actually released.

Trying to Map That Logic Onto Space

Mapping overlapping systems of pressure across environments

I began by mapping the same pressure categories onto analog space missions. At first glance, the structure appeared familiar:

Task pressure

Dense schedules, continuous checklists, operational discipline, and sustained cognitive demand tied to mission performance.Interpersonal pressure

Living and working with the same small group, navigating conflict that can’t be avoided, and managing emotional residue in a sealed social system.Environmental pressure

Monotony, sameness, confinement, limited spatial variation, and an interior world that rarely changes.

At this level, the logic seemed comparable to healthcare. But as I sat with it longer, it became clear that something was still missing, a condition that didn’t fit neatly into any of these categories.

Analog missions introduce an additional condition that doesn’t exist in the same way in healthcare: confinement combined with a lack of distraction. There is no casual escape, no background blur, no way to dilute attention through randomness or choice. Tasks continue, routines repeat, and focus remains largely unbroken.

This condition doesn’t replace the other pressures, it intensifies them. It creates an environment where pressure has nowhere to diffuse, and emotional load accumulates inwardly.

Confinement Without Distraction

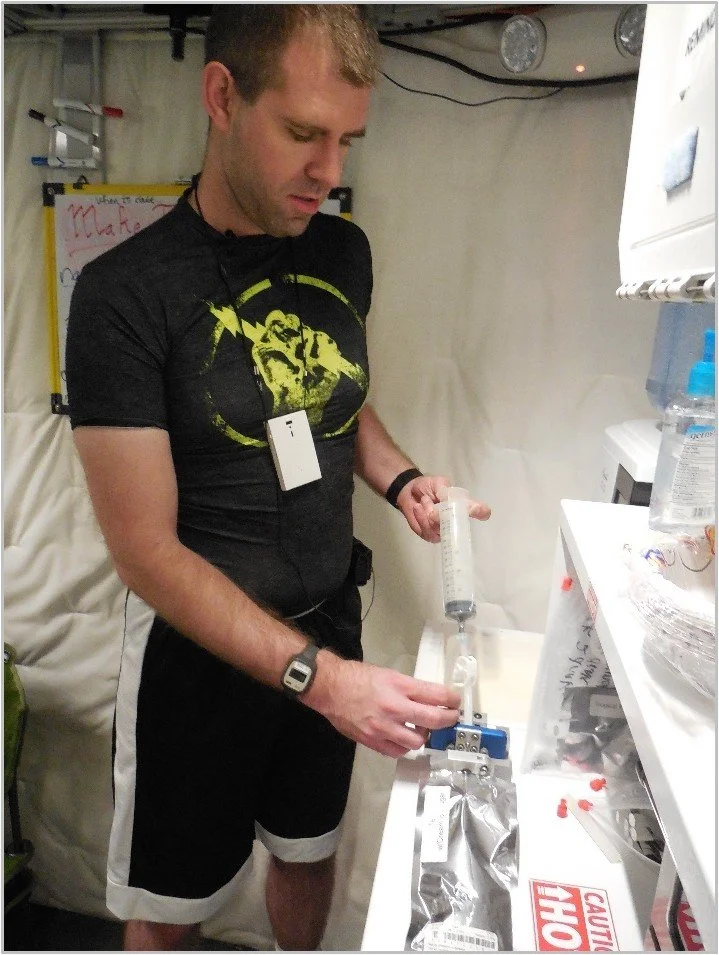

Andrzej Stewart - Continuous Focus Inside a Closed System

Image credits: Andrzej Stewart

The missing category is confinement without distraction. On top of task, interpersonal, and environmental pressures, analog missions introduce a condition defined by sustained focus and the absence of casual escape.

In these environments, there is too much focus and no distraction. No stepping away. No background blur. No easy way to diffuse attention. As a result, what often gets described as silence emerges, not as calm, but as a condition.

Silence here does not mean inactivity or rest. It means no interruption, no diffusion of attention, and no way for pressure to dissipate sideways. People are constantly busy, yet rarely interrupted. Tasks are continuous, routines are repetitive, and attention has nowhere to go but forward.

Without the small interruptions that diffuse emotional load on Earth, stepping outside, background noise, a change of scene, pressure has nowhere to go but inward. Over time, that inward accumulation becomes its own form of strain, shaping how emotion, conflict, and fatigue are experienced inside a closed system.

Pressure Behaves Similarly — Even When Inputs Differ

In healthcare settings, pressure builds through overload and overstimulation, dense task demands, interpersonal strain, and continuous sensory input layered with visual chaos.

In analog space missions, pressure builds through compression, task saturation, interpersonal tension, monotony, and attentional enclosure created by confinement without distraction.

The causes are different, but the result is familiar. In both cases, emotional pressure accumulates unless there is a way to release it. Whether driven by sensory overload or sensory deprivation, interpersonal strain or sustained focus, pressure does not disappear on its own, it builds.

This is why healthcare environments require architectural mechanisms to absorb and release pressure. And it raises a parallel question for extreme environments: if pressure behaves predictably, even when its sources differ, what kinds of spaces are needed to release it before it spreads?

Translating — Not Transplanting — Quiet Rooms

Quiet rooms work in healthcare because the problem they address is noise, overload, and overstimulation. These spaces allow pressure to be released in a controlled way, preventing it from spilling back into the system. In that sense, they function as architectural pressure-release mechanisms.

In extreme confinement, however, quiet already exists. Translating the same solution without modification would miss the psychological reality of the environment. What’s needed is not a quiet room, but a recalibration space, a modification of an existing typology, tuned to a different kind of pressure.

What I’m describing here does not yet exist as a defined space in analog missions; it’s a conceptual translation, drawn from healthcare precedents and reinterpreted for environments shaped by confinement and unrelieved focus.

In extreme confinement, quiet is not the goal, regulation is. Silence is already present. The challenge is unrelieved focus, confinement, and compression. A recalibration space responds to this by introducing a designed interruption — not escape, but intentional release.

In both healthcare and analog missions, these spaces function as mechanisms for controlled release. In healthcare, they relieve pressure created by overload and overstimulation. In analog missions, they relieve pressure created by confinement, monotony, and unrelieved focus. The sources differ, but the architectural responsibility remains the same: to provide a place where pressure can be released before it spreads through the system.

What a Recalibration Space Enables

A recalibration space allows pressure to be externalized rather than silently absorbed. It makes rising tension visible within the system and provides ways to release it before it spreads.

Such a space can support multiple modes of regulation, recognizing that people process pressure differently:

Physical release — movement, resistance, punching

Tactile engagement — deformable or responsive materials

Emotional expression — crying, vocal release

Verbal processing — optional connection to support on Earth

All opt-in. All controllable.

Unlike sleep quarters, which allow withdrawal, a recalibration space enables expression. It is not about avoiding the environment, but about returning to it in a more regulated state. By offering multiple pathways for release, physical, sensory, emotional, or verbal, architecture becomes an active participant in managing pressure, rather than a passive container for it.

Making Pressure Visible

It’s fair to ask why a dedicated space matters at all. After all, pressure can surface anywhere, in a bathroom, in a sleep quarter, behind a closed door. But those spaces allow withdrawal.

Recalibration spaces allow expression.

One hides pressure.

The other releases it before it spreads.

Closing Question

If pressure builds predictably in environments with no exit, even when its sources differ, at what point does recalibration become an architectural responsibility rather than an operational afterthought?

A Note on What Comes Next

Pressure doesn’t disappear when confinement ends. In many cases, it lingers, surfacing later as decision fatigue, overwhelm, or difficulty re-entering environments filled with choice, noise, and unpredictability.

The next piece looks at what happens after sustained pressure: when systems designed to remove friction suddenly give way to abundance, and when the hardest part isn’t endurance, but deciding again.

If you’d like to hear the full story in Andrzej’s own words, our conversation is on the Extreme Living podcast.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/5JZNjVQHCgKieq0qiWf501?si=0T1ZK4WQRg2woAc1fP25ZQ